It’s no secret that exercise can’t save you from the ill effects of prolonged sitting. But did you know that sitting actually damages your exercise?

It’s no secret that exercise can’t save you from the ill effects of prolonged sitting. But did you know that sitting actually damages your exercise?

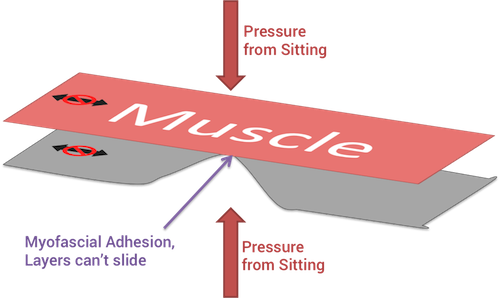

It’s true. Your butt isn’t designed to be a load-bearing surface. That prolonged pressure on your backside causes myofascial adhesion – tissue effects that damage your running posture and mobility.

Your Body the Cheeseburger

From bone to skin, the tissue of your body is stacked in layers. You’re probably already aware that those layers include muscles, ligaments, tendons, circulatory system components, and fat.

You can think of all these layers stacked up like a big double cheeseburger with bacon. I believe this analogy originated from the prolific Kelly Starrett.

But what many people don’t know, is that there’s also a layer called fascia, a thin, tough, fibrous yet elastic layer of connective tissue.

Your muscles and fascia with no sitting.

And most of what we typically describe as “muscle knots” are actually sticking points, or “adhesions”, between the fascia layer and the muscle. Your body is designed for all layers to easily slide relative to one another with no sticking. When fascia sticks to muscle (called a myofascial adhesion), bad stuff happens.

How Myofascial Adhesions Occur

You can stick your fascia to your muscle with two easy steps. First, be absolutely sedentary (at least in a local area). Second, add pressure perpendicular to the interface plane. Sitting hits both of these checkpoints hard along your glutes and hamstrings.

Prolonged sitting sticks your layers together so they can’t slide past each other easily. This means pain, poor form, and more injuries.

Hence, our favorite new maxim:

Sitting is the anti-massage.

These myofascial adhesions don’t just hurt (in weird remote places too), they also keep your body from working correctly.

Picture a game of tug-of-war, just you vs. your best friend. If you pull on the rope, it pulls him toward you, right? Now tie the middle of the rope to a flagpole between you two. Now your pulling doesn’t ever get to the other end of the rope, because the flag pole takes the load. This is exactly what happens with myofascial adhesions.

Let’s look at your hamstrings for example. Your hamstrings connect point A to B (your pelvis to the bones of your lower leg) and apply or absorb load. When free to slide past the fascia, they’ll do a great job of this. But connect them to the stationary fascia with a few adhesions, and everything gets screwed up.

Sticking your hamstrings to the surrounding fascia in a few places makes their load generation and application much less effective. When contracting, instead of pulling on your lower leg as desired, your hamstrings are wasting energy trying to break myofascial adhesions.

This is how myofascial adhesions cause reduced range of motion, destroy your force application ability, and increase likelihood of injury.

When Adaptation Backfires

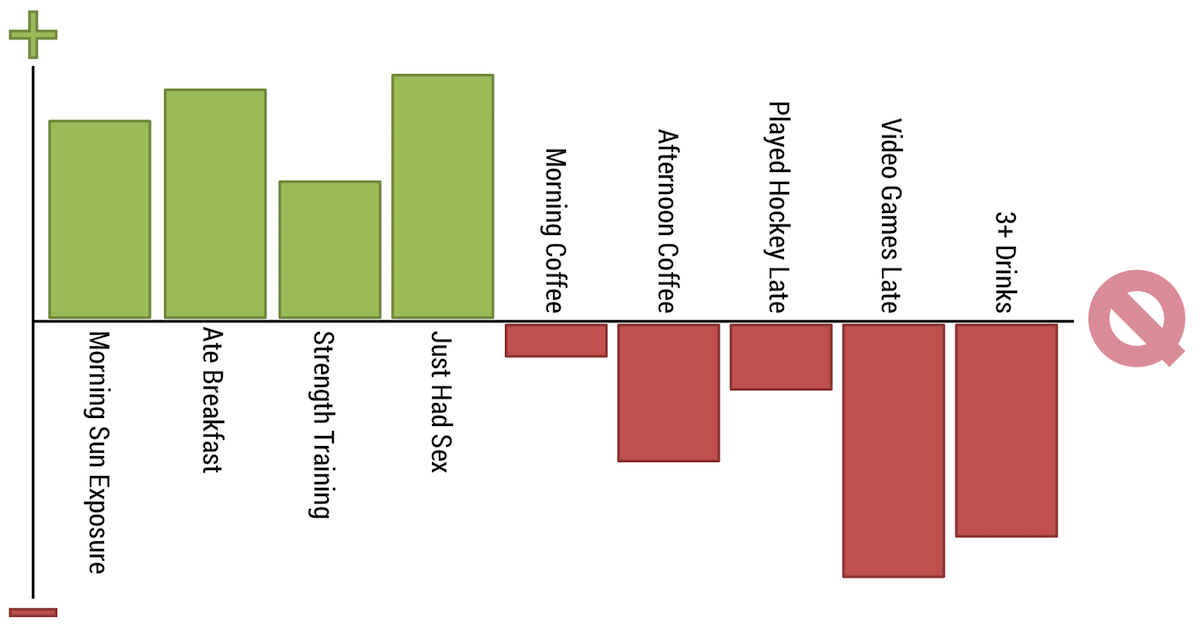

Myofascial adhesions are bad, but it gets even worse. Sitting displaces lots of healthy movements like squatting or lunging, and this sends your body a clear message. A message that you would be better off with a body built for sitting. So over time, your tissues shorten and lose their rate of force development.

Your body thinks it’s doing you a favor by adapting to be better at the stuff you do most of the time. But this absolutely backfires.

Shortened, slowed, sticky tissue prevents you from achieving the form necessary for performing athletically without injury.

All Together: How Sitting Ruins Running

Running is a complicated biomechanics maneuver. This image shows the many positions your body adopts in stride:

Now add in some terrain variation and velocity changes, and it’s easy to see that your body takes dozens of different forms on even a simple jog.

This is a lot for your brain to handle, but it does a marvelous job. It takes information from incoming signals and makes hundreds of calculations per second before sending instructions out to your muscles (we’ve seen before how shoes wreck that control loop).

Your brain is doing the best it can, but with all the tissue damage caused by sitting – myofascial adhesion and tissue atrophy – it will have to make compromises. Your glutes and hamstrings can’t develop force fast enough because they’re stuck to fascia. Your hip flexors can’t stretch far enough to let your legs trail appropriately.

You’ll end up running with poor form because your body can’t handle running the right way.

Couple that poor form with all the imbalances and tissue damage you’ve accumulated in a chair, and the situation is almost guaranteed to cause injury.

Of course, this logic extends to all athletic endeavors, not just running. Kicking a soccer ball is much more dangerous after decades of chronic sitting, as many 40 year olds with a tweaked-something-or-other can attest to.

Reclaim Your Tissue Health and Running Form

As always, we recommend ditching your chair, at least part time. Here’s a smart transition plan.

Staying hydrated is also critically important to avoiding myofascial adhesions. So get your salts and water.

Foam rolling and massage will go a long way toward reversing years of damage as well. I love love LOVE the rumble roller, but if you’re new to the game, you may want to start with something a little smoother (get the 26″ model). The more you roll (both frequency and body coverage), the better you’ll feel, but the biggest targets here should be your glutes and hamstrings.

Restoring your hip flexors will take a little more work and pain – the best place to start is with the couch stretch.

In short, here’s your action plan:

- Sit less and stand smart.

- Stay hydrated.

- Foam roll your glutes and hamstrings.

- Stretch your hip flexors.

- Enjoy better health and reduced chance of injury in your athletic endeavors.

The post Sticking Points: How Your Chair is Ruining Your Running appeared first on Quitting Sitting.